JACK TROUT

"TROUT ON STRATEGY"

To my wife, who had to live with me while I wrote all my books

PREFACE

It's been a long journey.

Starting at General Electric and winding through hundreds of companies in the United States and all over the globe, I've had the rare opportunity to understand what makes up success or failure in business.

These observations have been carefully catalogued and presented in 10 books and endless lectures to thousands of business people in every corner of the world.

What I've learned over and over again is that success isn't about having the right people, the right attitude, the right tools, the right role models, or the right organization. They all help, but they don't put you over the top.

It's all about having the right strategy.

That's because strategy sets the competitive direction, strategy dictates product planning, strategy tells you how to communicate internally and externally, strategy tells you on what to focus.

That's why it is so important to understand what strategy is all about. The better you understand strategy, the better you'll be able to select the right strategy for success. And, conversely, the better you'll be able to avoid the big trouble it's easy to encounter in our era of killer competition.

There has been no shortage of advice on this subject. In the past 30 years there have been 21,955 books written about strategic planning and marketing. One author will talk about sustainable competitive advantage. Another will announce that this idea is on its way out. One author talks about the importance of case studies. Another says that case studies shouldn't decide your strategy. And of course there is no end to jargon, such as dynamic advantage, conjoint analysis,

competitive dynamics, coevolution, and my favorite, sustainable competitive disadvantage. All of this generates nothing but confusion.

But what makes things far worse is the fact that there are those who would say that strategy is one thing and marketing is another. But the truth is that they must be combined if you are to be successful. Marketing is what drives a business. And a great business strategy without proper marketing will often fail in a highly competitive world. To better understand this, consider the following example:

A small software company has come up with a better way to conduct project management. It uses a different methodology that deals with the uncertainties that surround most projects. One could say this company has a competitive advantage strategy with a superior product. All management has to do is hand the product to the marketing department staff and instruct them to tell the world about this wonderful software and why it is better. This approach would fail. The problem is that this company has two very large, established competitors, as well as a number of smaller ones. They will quickly attack this smaller company and attempt to exclude it from the game. Their strategy will be to make their customers nervous about turning their project management over to an unknown. To get into the game, this company must come up with a marketing program that positions its new software as "The next generation of project management software." Everything the company does must drive this idea into the minds of its customers. It is establishing this "next generation" perception that will be the key to its success or failure. This will offset the natural concerns of dealing with an unknown. At the same time, no one wants to buy what is perceived to be an obsolete product.As you can see by this example, the next-generation marketing of this improved software exploited a basic positioning principle that states that it is better to be first than to be better. The marketing is driving the business strategy. Thus my definition of strategy: What makes you unique and what is the best way to put that difference into the minds of your customers and prospects.

In this example, the new form of software that dealt with uncertainties was unique. The next-generation concept was the best way into the minds in the marketplace.

While I have written endlessly about success and failure, I've never focused on what the essence of good strategy is all about. So I went back and extracted from my many books the key guidelines to doing the right thing. Unlike my usual fare, there are a few examples but no

detailed case histories in these extracts. There are mostly the important principles to follow.

It's a short course on what I've learned about strategy in my long journey through the business world.

Jack Trout

Strategy Is All about Survival

Copyright © 2004 by Jack Trout. Click here for terms of use.

Using good strategy is how you survive in a world of killer competition. Using good strategy is how you survive what I call the tyranny of choice.

In the beginning, choice was not a problem. When our earliest ancestors wondered "What's for dinner?" the answer wasn't very complicated. It was whatever animal in the neighborhood they could run down, kill, and drag back to the cave.

Today you walk into a cavernous supermarket and gaze out over a sea of different types and cuts of meats that someone else has run down, killed, dressed, and packaged for you.

Your problem is no longer catching dinner. Your problem is to try to figure out what to buy of the hundreds of different packages staring back at you from the case. Red meat? White meat? The other white meat? Make-believe meat?

But that's only the beginning. Now you have to figure out what part of the animal you want. Loin? Chops? Ribs? Legs? Rump?

And what do you bring home for those family members who don't eat meat?

FISHING FOR DINNER

For that early ancestor, catching a fish was simply a matter of sharpening a stick and hoping to get lucky.

Today it can mean drifting into a Bass Pro Shop or an L.L. Bean or a Cabela's or an Orvis and being dazzled with a mind-boggling array of rods, reels, lures, clothing, boats, you name it.

At Bass Pro Shop's 300,000-square-foot flagship store in Springfield, Missouri, they will give you a haircut and then make a fishing lure out of the clippings for you.

Things have come a long way from that pointed stick.

GOING TO DINNER

Today many people figure it's better to have someone else figure out what's for dinner. But figuring out where to go is no easy decision in a place like New York City.

That's why, in 1979, Nina and Tim Zagat created the first New York restaurant survey to help us answer that difficult question of choice.

Today the pocket-sized Zagat Survey guides have become bestsellers, with 100,000 participants rating and reviewing restaurants in more than 40 major U.S. and foreign cities.

AN EXPLOSION OF CHOICE

What has changed in business over recent decades is the amazing proliferation of product choices in just about every category. It's been estimated that there are 1 million stock keeping units(SKUs) out there in America. An average supermarket has 40,000 SKUs. Now for the stunner - an average family gets 80 to 85 percent of its needs from 150 SKUs. That means there's a good chance you'll ignore 39,850 items in that store.

Buying a car in the 1950s meant the choice of a model from GM, Ford, Chrysler, or American Motors. Today you have your pick of cars, from GM, Ford, DaimlerChrysler, Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen, Fiat, Nissan, Mitsubishi, Renault, Suzuki, Daihatsu, BMW, Hyundai, Daiwa, Mazda, Isuzu, Kia, and Volvo. There were 140 motor vehicle models available in the early 1970s. There are 260 today.

Even in as thin a market as $175,000 Ferrari-type sports cars, there is a growing competition. You have Lamborghini, a new Bentley sports car, Aston Martin, and a new Mercedes called the Vision SLR.

Three decades ago, most manufacturers offered half a dozen vehicle styles. Today, there are so many(sport utility vehicles [SUVs], roadsters, hatchbacks, coupes, minivans, wagons, pickups, and "crossovers") that companies are being forced to outsource manufacturing. A manufacturer in Austria now makes BMWs, Jeeps, Mercedeses, and Saabs. Good old Henry Ford is probably looking down on this with some amusement. His concept was "all black and all the same."

And the proliferation in the choice of tires for these cars is even worse. It used to be Goodyear, Firestone, General, and Sears. Today you have the likes of Goodyear, Bridgestone, Cordovan, Michelin, Cooper, Dayton, Firestone, Kelly, Dunlop, Sears, Multi-Mile, Pirelli, General, Armstrong, Sentry, Uniroyal, and 22 other brands.

The big difference is that what used to be national markets with local companies competing for business has become a global market with

everyone competing for everyone's business everywhere.

CHOICE IN HEALTH CARE

Consider something as basic as health care. In the old days you had your doctor, your hospital, Blue Cross, and perhaps Aetna/US Healthcare, Medicare, or Medicaid. Now you have to deal with new names such as MedPartners, Cigna, Prucare, Columbia, Kaiser, Wellpoint, Quorum, Oxford, Americare, and Multiplan, and concepts like health maintenance organizations(HMOs), peer review organizations(PROs), physician hospital organizations(PHOs), and preferred provider organizations(PPOs).

CHOICE IS SPREADING

What we just described is what has happened to the U.S. market, which, of the world's markets, has by far the most choice(because our citizens have the most money and the most marketing people trying to get it from them).

Consider an emerging nation such as China. After decades of buying generic food products manufactured by state-owned enterprises, China's consumers now can choose from a growing array of domestic and foreign brand-name products each time they go shopping. According to a recent survey, a national market for brand-name food products has already begun to emerge. Already China has 135 national food brands from which to pick. They've got a long way to go, but they are on their way to some serious tyranny.

Some markets are far from emerging. Countries such as Liberia, Somalia, North Korea, and Tanzania are so poor and chaotic that choice is but a gleam in people's eyes.

THE LAW OF DIVISION

What drives choice is the law of division, which was first published in the 1993 book I wrote with Al Ries, The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing.

Like the computer, the automobile started off as a single category. Three brands(Chevrolet, Ford, and Plymouth) dominated the market. Then the category divided.

Today a wired household has over 150 channels from which to choose. And they are threatening us with "streaming video" that promises to make the cable industry's dream of a 500-channel universe look pathetically unambitious. With all that, if you flip through the channels and try to find something to watch, by the time you find it the show will be over.

Division is a process that is unstoppable. If you have any doubts,

consider the accompanying table on the explosion of choice.

THE "CHOICE INDUSTRY"

All this has led to an entire industry dedicated to helping people with their choices. We've already talked about Zagat's restaurant guides.

The Explosion of Choice

|

Item

|

Early 1970s

|

Late 1990s

|

| Vehicle models

|

140

|

260

|

| KFC menu items

|

7

|

14

|

| Vehicle styles

|

654

|

1,121

|

| Frito-Lay chip varieties

|

10

|

78

|

| SUV styles

|

8

|

38

|

| Breakfast cereals

|

160

|

340

|

| PC models

|

0

|

400

|

| Pop-Tart varieties

|

3

|

29

|

| Software titles

|

0

|

250,000

|

| Soft drink brands

|

20

|

87

|

| Web sites

|

0

|

4,757,894

|

| Bottled water brands

|

16

|

50

|

| Movie releases

|

267

|

458

|

| Milk types

|

4

|

19

|

| Airports

|

11,261

|

18,202

|

| Colgate toothpaste varieties

|

2

|

17

|

| Magazine titles

|

339

|

790

|

| Mouthwashes

|

15

|

66

|

| New book titles

|

40,530

|

77,446

|

| Dental flosses

|

12

|

64

|

| Community colleges

|

886

|

1,742

|

| Prescription drugs

|

6,131

|

7,563

|

| Amusement parks

|

362

|

1,174

|

| Over-the-counter pain relievers

|

17

|

141

|

| TV screen sizes

|

5

|

15

|

| Levi's jean styles

|

41

|

70

|

| Houston TV channels

|

5

|

185

|

| Running shoe styles

|

5

|

285

|

| Radio stations

|

7,038

|

12,458

|

| Women's hosiery styles

|

5

|

90

|

| McDonald's menu items

|

13

|

43

|

| Contact lens types

|

1

|

36

|

Everywhere you turn, someone is offering advice on things like which of the 8000 mutual funds to buy. Or how to find the right dentist in St. Louis. Or the right MBA program from among hundreds of business schools.(Will it help you get a Wall Street job?)

Magazines like Consumer Reports and Consumers Digest deal with the onslaught of products and choices by rotating the categories on which they report. The only problem is that they go into so much detail that you're more confused than when you started.

Consumer psychologists say this sea of choices is driving us bonkers. Consider what Carol Moog has to say on the subject: "Too many choices, all of which can be fulfilled instantly, indulged immediately, keeps children - and adults - infantile. From a marketing perspective, people stop caring, get as fat and fatigued as foie gras geese, and lose their decision-making capabilities. They withdraw and protect against the overstimulation; they get 'bored.'"

CHOICE CAN BE CRUEL

The dictionary defines tyranny as absolute power that often is harsh or cruel.

So it is with choice. With the enormous competition, markets today are driven by choice. The customer has so many good alternatives that you pay dearly for your mistakes. Your competitors get your business and you don't get it back very easily. Companies that don't understand this will not survive.(Now that's cruel.)

Just look at some of the names on the headstones in the brand graveyard: American Motors, Burger Chef, Carte Blanche, Eastern Airlines, Gainesburgers, Gimbel's, Hathaway shirts, Horn & Hardart, Mr. Salty Pretzels, Philco, Trump Shuttle, VisiCalc, Woolworth's.

And this is only a short list of names that are no longer with us.

AND IT WILL ONLY GET WORSE

Don't bet that all this will calm down. I feel that it will get worse for the simple reason that choice appears to beget more choice.

In a book titled Faster, author James Glieck outlines what can only be called a bewildering future, which he describes as "The acceleration of just about everything." Consider the following scenario:

This proliferation of choice represents yet another positive feedback loop - a whole menagerie of such loops. The more information glut bears down on you, the more Internet "portals" and search engines and infobots arise to help by pouring information your way. The moreLadies and gentlemen, we haven't seen anything yet.

WHAT REALLY WORKS

Nitkin Nohria, William Joyce, and Bruce Roberson conducted what was described in the Harvard Business Review(July 2003) as "the most rigorous study of management practices ever undertaken." They reported that what really works is not CRM, TQM, BPR, and other tools or fads. Superior performance in this competitive world is all about mastering business basics. Vince Lombardi of Green Bay Packers fame would have described it as good blocking and tackling.

Their number-one basic was "Devising and maintaining a clearly stated, focused strategy." To achieve excellence in strategy is to be clear about what the strategy is and to constantly communicate it to customers, employees, and shareholders. It's a simple, focused value proposition. In other words, what's the reason to buy from you instead of one of your competitors?

THE DEFINITION OF STRATEGY

If using good strategy is how you are to survive, a good starting point is to look at the definition of strategy, as found in Webster's New World Dictionary:

The science of planning and directing large-scale military operations. Of maneuvering forces into the most advantageous position prior to actual engagement with the enemy.You'll notice that this is a military word with the enemy in mind. If you are going to seek that "most advantageous position," you must first study, understand, and maneuver around the battleground. And that battleground is in the minds of your customers and prospects.

SUMMATION

••••••••••••••••••••••••••

In a tough world, using strategy is how you survive.

class="toc_h">Strategy Is All about Perceptions

Positioning is how you differentiate yourself in the mind of your prospect. It's also a body of work on how the mind works in the process of communication.

The first words on this important subject go back to 1969, when I wrote an article in Industrial Marketing Management titled "Positioning Is a Game People Play in Today's Me-Too Marketplace."(That's when choice first began to rear its ugly head.)

Here's an untold secret. I chose the word positioning because of the dictionary definition of strategy offered in the previous chapter: Finding the most advantageous position against the enemy.

Then, in 1981, my ex-partner Al Ries and I published the very popular Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind. In 1996, I wrote The New Positioning: The Latest on the World's #1 Business Strategy. This latter book made the simple case that your business strategy will succeed or fail depending on how well you understand the five most important elements in the positioning process. Here's a short course on each of these elements.

1. MINDS ARE LIMITED

Like the memory bank of a computer, the mind has a slot or position for each bit of information it has chosen to retain. In operation, the mind is a lot like a computer.

But there is one important difference. A computer has to accept what you put into it. The mind does not. In fact, it's quite the opposite. The mind rejects new information that doesn't compute. It accepts only new information that matches its current state of mind.

AN INADEQUATE CONTAINER

Not only does the human mind reject information that does not match its prior knowledge or experience, it doesn't have much prior knowledge or experience to work with.

In our overcommunicated society, the human mind is a totally inadequate container.

According to Harvard psychologist George A. Miller, the average human mind cannot deal with more than seven units at a time, which is why seven is a popular number for lists that have to be remembered. Seven-digit phone numbers, the Seven Wonders of the World, seven-card stud, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Ask someone to name all the brands he or she remembers in a given product category. Rarely will anyone name more than seven. And that's

for a high-interest category. For low-interest products, the average consumer can usually name no more than one or two brands.

Try listing all ten of the Ten Commandments. If that's too difficult, how about the seven danger signals of cancer? Or the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse?

If our mental storage bowl is too small to handle questions like these, how in the world are we going to keep track of all those brand names that have been multiplying like rabbits over the years?

THE PRODUCT LADDER

To cope with the product explosion, people have learned to rank products and brands in the mind. Perhaps this can best be visualized by imagining a series of ladders in the mind. On each step is a brand name. And each different ladder represents a different product category.

Some ladders have many steps.(Seven is many.) Others have few, if any.

A competitor that wants to increase its share of the business must either dislodge the brand above(a task that is usually impossible) or somehow relate its brand to the other company's position.

Yet too many companies embark on marketing and advertising programs as if the competitor's position did not exist. They advertise their products in a vacuum and are disappointed when their messages fail to get through.

Moving up the ladder in the mind can be extremely difficult if the brands above have a strong foothold and no leverage or positioning strategy is applied.

An advertiser who wants to introduce a new product category must carry in a new ladder. This, too, is difficult, especially if the new category is not positioned against the old one. The mind has no room for what's new and different unless it's related to the old.

That's why if you have a truly new product, it's often better to tell the prospect what the product is not, rather than what it is.

The first automobile, for example, was called a horseless carriage, a name that allowed the public to position the concept against the existing mode of transportation.

Phrases like off-track betting, lead-free gasoline, and sugar-free soda are all examples of how new concepts can best be positioned against the old.

THE NEWS FACTOR

One other way of overcoming the mind's natural stinginess when it comes to accepting new information is to work hard at presenting your message as important news.

Too many advertisers try to entertain or be clever. In so doing, they often overlook the news factor in their story.

The Roper Starch research people can demonstrate that headlines which contain news score better in readership than those that don't. Unfortunately, most creative people see this kind of thinking as old news.

If people think you've got an important message to convey, generally they'll open their eyes or ears long enough to absorb what you've got to say.

2. MINDS HATE CONFUSION

Human beings rely more heavily on learning than any other species that has ever existed.

"Learning is the way animals and human beings acquire new information," says a scientist at Columbia University's Center for Neurobiology and Behavior. "Memory is the way they retain that information over time."

"Memory is not just your ability to remember a phone number," says experimental psychologist Lynne Reder, who studied memory at Carnegie Mellon University. "Rather, it's a dynamic system that's used in every other facet of thought processing. We use memory to see. We use it to understand language. We use it to find our way around."

So if memory is so important, what's the secret of being remembered?

KEEP IT SIMPLE

When asked what single event was most helpful to him in developing the theory of relativity, Albert Einstein is reported to have answered: "Figuring out how to think about the problem."

John Sculley, former chairman of Apple computer, put it this way:

Everything we have learned in the industrial age has tended to create more and more complication. I think that more and more people are learning that you have to simplify, not complicate. That is a very Asian idea - that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.Professional communicators, such as the network broadcasters, understand this principle very well. They keep their word selection very simple.(More on this in Chapter 6.)

THE PROBLEM OF COMPLEXITY

We tend to think of boredom as arising from a lack of stimuli. A sort of information underload.

But more and more commonly, boredom is arising from excessive stimulation or information overload.

Information, like energy, tends to degrade into entropy - into just noise, redundancy, and banality. To put it another way, the fast horse of information outruns the slow horse of meaning.

Complicated answers don't help anybody. For instance, every executive wants information, because the difference between a decision and a guess often comes down to information. But today's executives don't want to be buried alive in printouts and reports.

PRODUCTS WITH MORE

We have this terrific word for new products: more.

Marketing people love to talk about convergence, the process whereby technologies are merged and wondrous new products are introduced with more and more features. Here's an early list of casualties:

AT&T's EO Personal Communicator, a cellular phone, fax, electronic mail device, personal organizer, and pen-based computer Okidata's Doc-it, a desktop printer, fax, scanner, and copier Apple's Newton, a fax, beeper, calendar-keeper, and pen-based computer Sony's multimedia player, with display screen and interactive keyboardBut those are simple compared to Bill Gates's version of the wallet of the future. He sees it as a device that will combine or replace keys, charge cards, personal identification, cash, writing implements, a passport, and pictures of the kids. It also would have a global positioning system so you can always tell where you are.

Will any of these products make it?

Not likely. They are too confusing and too complex. Most of the people in the world still can't figure out how to record on their VCRs.

People resist that which is confusing, and cherish that which is simple. They want to push a button and watch it work.

CONFUSING CONCEPTS

The basic concepts behind some products predict failure. Not because they don't work but because they don't make sense.

Consider Mennen's Vitamin E deodorant. That's right, you sprayed a vitamin under your arm.

Present this concept to a group of consumers, and, guaranteed, you'll get a laugh. It doesn't make sense unless you want the healthiest,

best-fed armpits in the nation. No one is going to try to figure that one out.

It quickly failed.

Consider Extra-Strength Maalox Whip Antacid. That's right, you sprayed a glob of cream whip on a spoon and took it for your heartburn.

This had a hard time even getting on the shelves, as the druggists laughed the salespeople out of the store. Antacids are tablets or liquids, not whipped cream.

At the time all it did was give the manufacturer, William H. Rorer, a costly case of indigestion.

Confusion strikes again.

3. MINDS ARE INSECURE

Aristotle would have been a lousy ad man. Pure logic is no guarantee of a winning argument.

Minds tend to be emotional, not rational.

Why do people buy what they buy? Why do people act the way they do in the marketplace? According to psychologists Robert Settle and Pamela Alreck, in their book Why They Buy, customers don't know, or they won't say.

When you ask people why they made a particular purchase, the responses they give are often not very accurate or useful.

That may mean they really do know, but they're reluctant to tell you the right reason.

More often, they really don't know precisely what their own motives are.

Even when it comes to recall, minds are insecure and tend to remember things that no longer exist. Recognition of a well-established brand often stays high over a long time period, even if advertising support is dropped.

BUYING WHAT OTHERS BUY

My experience is that people don't know what they want.(So why ask them?)

More times than not, people buy what they think they should have. They're sort of like sheep, following the herd.

Do most people really need a four-wheel-drive vehicle?(No.) If they did need them, why didn't they become popular years ago?(Not fashionable.)

The main reason for this kind of behavior is insecurity, a subject about which many scientists have written extensively.

FIVE FORMS OF PERCEIVED RISK

Minds are insecure for many reasons. One reason is perceived risk in doing something as basic as making a purchase.

Behavioral scientists say there are five forms of perceived risk:

1.Monetary risk. There's a chance I could lose my money on this. 2.Functional risk. Maybe it won't work, or do what it's supposed to do. 3.Physical risk. It looks a little dangerous. I could get hurt. 4.Social risk. I wonder what my friends will think if I buy this? 5.Psychological risk. I might feel guilty or irresponsible if I buy this.FOLLOWING THE HERD

One of the most interesting pieces of work on why people follow the herd was written by Robert Cialdino. He talks of the principle of social proof as a potent weapon of influence:

This principle states that we determine what is correct by finding out what other people think is correct. The principle applies especially to the way we decide what constitutes correct behavior. We view a behavior as correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it. The tendency to see an action as appropriate when others are doing it works quite well normally. As a rule, we will make fewer mistakes by acting in accord with social evidence than by acting contrary to it. Usually, when a lot of people are doing something, it is the right thing to do. This feature of the principle of social proof is simultaneously its major strength and its major weakness. Like the other weapons of influence, it provides a convenient shortcut for determining the way to behave but, at the same time, makes one who uses the shortcut vulnerable to the attacks of profiteers who lie in wait along its path.THE TESTIMONIAL

When people are uncertain, they often will look to others to help them decide how to act.

That's why one of the oldest devices known to advertising is the testimonial.

A testimonial attacks the insecure mind on several emotional fronts - a trifecta of vanity, jealousy, and fear of being left out.

Stanley Resor, one-time head of J. Walter Thompson, called it "the spirit of emulation." Said Resor, "We want to copy those whom we deem superior in taste or knowledge or experience."

Today's favorite testimonials involve the athletes. Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods are the best of the breed.

THE BANDWAGON

Creating a bandwagon effect is another powerful technique for dealing with the insecure mind.

Originally, a bandwagon was an elaborately decorated wagon used to transport musicians in a parade. Today it has come to mean any cause or trend that takes an increasing number of people along for the ride.

Polls and panels always make good authority figures to create the bandwagon.(J.D. Powers surveys are a good example.)

Another bandwagon strategy for dealing with the insecure mind is that of the "fastest-growing" or "largest-selling." It says that others obviously think we have a pretty good product.

THE HERITAGE

Marketers also display their tradition and culture as a way of getting you on their bandwagon.(After all, how can a mere consumer argue with heritage?)

As early as 1919, a Steinway piano was being described in an advertisement as "the instrument of the immortals."

Cross trumpets its pens and mechanical pencils as "flawless classics, since 1846."

Glenlivet positions itself as "the father of all Scotch. His Majesty's Government bestowed on The Glenlivet Distillery the very first license under The Act of 1823 to distill single malt whisky in the Highlands."

Coke has exploited its heritage in inventing the cola by calling itself "the real thing." That is the company's most powerful strategy.

4. MINDS DON'T CHANGE

There has always been a general feeling in the marketing industry that new-product advertising should generate higher interest than advertising for established brands.

But it turns out that we're actually more impressed by what we already know(or buy) than by what's "new."

One research organization, McCollum Spielman, has tested more than 22,000 TV commercials over 23 years. Almost 6000 of those commercials were for new products in 10 product categories.

What did they learn? Greater persuasion ability and attitude shifts - the so-called new-product excitement - were evident in only 1 of the 10 categories(pet products) when comparing new brands to established

brands.

In the other 9 categories - ranging from drugs to beverages to personal hygiene items - there was no real difference, no burst of excitement, enabling consumers to distinguish between established brands and new brands.

With thousands of different commercials across hundreds of different brands, you can pretty much rule out "creativity" as the difference in persuasion. It comes back to what we're familiar with, what we're already comfortable with.

TRYING TO CHANGE ATTITUDES

In the book The Reengineering Revolution, MIT professor-turned-consultant Michael Hammer calls human beings' innate resistance to change "the most perplexing, annoying, distressing, and confusing part" of reengineering.

To help us better understand this resistance, a book titled Attitudes and Persuasion offers some insights. Written by Richard Petty and John Cacioppo, it spends some time on "belief systems." Here's their take on why minds are so hard to change:

The nature and structure of belief systems is important from the perspective of an informational theorist, because beliefs are thought to provide the cognitive foundation of an attitude. In order to change an attitude, then, it is presumably necessary to modify the information on which that attitude rests. It is generally necessary, therefore, to change a person's beliefs, eliminate old beliefs, or introduce new beliefs.And you're going to do all that with a 30-second commercial?

WHAT PSYCHOLOGISTS SAY

The Handbook of Social Psychology reinforces how tough it is to change attitudes:

Any program to change attitudes offers formidable problems. The difficulty of changing a person's basic beliefs, even through so elaborate and intense a procedure as psychotherapy, becomes understandable, as does the fact that procedures that are effective in changing some attitudes have little effect on others.And what makes things even worse is that truth has no real bearing on these issues. Check out this observation:

People have attitudes on a staggeringly wide range of issues. They seem to know what they like(and especially dislike) even regarding objects about which they know little, such as Turks, or which have little relevance to their daily concerns, like life in outer space.So, to paraphrase an old TV show, if your assignment, Mr. Phelps, is to change people's minds, don't accept the assignment.

5. MINDS CAN LOSE FOCUS

In days gone by, most big brands were clearly perceived by their customers. The mind, like a camera, had a very clear picture of what its favorite brands were all about.

When Anheuser-Busch proudly proclaimed that "This Bud's for you," the customer knew exactly what was being served.

The same went for Miller High Life, or plain old Coors beer.

But in the past decade, Budweiser flooded the market with a vast variety of regular, light, draft, clear, cold-brewed, dry-brewed, and ice-brewed beers.

Now the statement "This Bud's for you" can only elicit the question, "Which one do you have in mind?"

That clear perception in the mind is now badly out of focus. It's no wonder the King of Beers is starting to lose its following.

THE LINE EXTENSION TRAP

Loss of focus is really all about line extension. And no issue in marketing is so controversial.

In our 1972 Advertising Age articles, Al Ries and I cautioned companies not to fall into what we called "the line extension trap."

Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind contains two chapters on the problem of line extension.

In The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing, it became the single most violated law.

Not that our lack of approval has slowed anyone down. In fact, quite the opposite has been true. "Extending brand equity" has become all the rage, as companies like Coca-Cola talk about concepts such as "megabrands."

For years we were the lonely voices railing against line extension. Even the Journal of Consumer Marketing noticed this: "Ries and Trout stand alone as the only outright critics of the practice of brand extension."(Our minds don't change.)

That lasted until the Harvard Business Review(November-December 1994) rendered its verdict: "Unchecked product-line extension can weaken a brand's image, disturb trade relations, and disguise cost increases."

Keep it up, guys.

The difference in views on this subject is essentially a matter of perspective. Companies look at their brands from an economic point of view. To gain cost efficiencies and trade acceptance, they are quite willing to turn a highly focused brand, one that stands for a certain type of product or idea, into an unfocused brand that represents two or three or more types of products or ideas.

I look at the issue of line extension from the point of view of the mind. The more variations you attach to the brand, the more the mind loses focus. Gradually, a brand like Chevrolet comes to mean nothing at all.

Scott, the leading brand of toilet tissue, line-extended its name into Scotties, Scottkins, ScotTowels. Pretty soon "Scott" flunked the shopping-list test.(You can't write down "Scott" and have it mean anything.)

DANGER: A WELL-FOCUSED SPECIALIST

Things would have been fine in the land of Scott if the likes of Mr. Whipple and his squeezable Charmin tissue hadn't arrived on the scene.(The more you lose focus, the more vulnerable you become.) It didn't take long for Charmin to become the number-one tissue.

The course of business history seems to verify our concerns.

For years, Procter & Gamble's Crisco brand was the leading shortening. Then the world turned to vegetable oil. Of course, Procter & Gamble turned to Crisco Oil.

So who was the big winner in the corn-oil melee? That's right, Mazola.

Then Mazola noticed the success of a no-cholesterol corn-oil margarine. So Mazola introduced Mazola Corn Oil Margarine.

So who was the winner in the corn-oil-margarine category? You're right, it was Fleischmann's.

In each case, the specialist or the well-focused competitor was the winner.

THE SPECIALIST'S WEAPONS

Here are some thoughts on why the specialist brand appears to make such an impression on the mind.(More on this in Chapter 5.)

First, the specialist can focus on one product, one benefit, one message. This focus enables the marketer to put a sharp point on the message that quickly drives it into the mind. Some examples:

Domino's Pizza can focus on its home delivery. Pizza Hut has to talk about both home delivery and sit-down service. Duracell can focus on long-lasting alkaline batteries. Eveready had to talk about flashlight, heavy-duty, rechargeable, and alkaline batteries.(Then Eveready gotAnother weapon of the specialist is the ability to be perceived as the expert or the best. Intel is the best in microchips. Philadelphia is the best brand in cream cheese.(The original, so to speak.)

Finally, the specialist can become the generic for the category:

Xerox became the generic word for copying.("Please xerox that for me.") Federal Express became the generic word for overnight delivery.("I'll FedEx it to you.") 3M's Scotch tape became the generic word for cellophane tape.("I'll scotch-tape it together.")Even though the lawyers hate it, making the brand name a generic is the ultimate weapon in the marketing wars. But it's something only a specialist can do. The generalist can't become a generic.

Nobody ever says, "Get me a beer from the GE."

SUMMATION

••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Perception is reality.

Don't get confused by facts.

Strategy Is All about Being Different

As you read in Chapter 2, in the land of positioning, a successful strategy is based on finding a way to be different from your sea of competitors. What is the reason to buy your brand instead of another?

While others have written about the importance of "differentiation," few if any have presented the many ways you can do it. This is why I cowrote the book Differentiate or Die. But before we get to the how-to-do-it strategies, it's important to focus on the how-not-to-do-it strategies. In other words, quality and customer orientation are rarely differentiation ideas.

THE WAR ON QUALITY

Yes, the 1990s witnessed a war on quality. Business leaders demanded tools and techniques to measure it. An army of gurus and academics marched forth with books and endless diatribes on how to define, predict, and ensure this elusive creature called quality.

On they came, a numbing maze of acronyms and buzzwords: the

Seven Old Tools, the Seven New Tools, TQM, SPC, QFD, CQL, and just about any other combination of three letters you could string together.

In 1993 alone, there were 422 books in print with the word quality in the title. Today, there are half as many.(We must have won the war.)

Survey after survey today acknowledges that consumers see quality improvements all around them. Cars are better made. Small appliances last longer. Computers come with instruction manuals in simple English.

The editorial director at polling firm Roper Starch Worldwide explains it this way:

All brands have to work harder to get ahead today. They keep upping the ante to meet consumers' needs. The consumer is still king. And it doesn't look like the equation is going to change anytime soon. Consumers have not slacked off in their demands as the economy has improved. If anything, they've grown more demanding.It sounds as though quality only keeps you in the game.

THE WAR FOR CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

If quality were a war, then the assault on the customer would be Armageddon.

A landmark study published in Harvard Business Review argued that companies could improve profits by at least 25 percent by reducing customer defections by 5 percent. Whoa, Nellie. You could hear the alarm bells going off in boardrooms across the land.

Seminars, books, and counselors told us 1001 ways to dazzle, love, partner with, and just plain hang on to that person called a customer.

We were told the customer is a collaborator. The customer is the CEO. The customer is king. The customer is a butterfly.(Don't even ask.)

Customer feedback meant every complaint was a gift. Better aftermarketing would keep a customer for life. Learning how to manage in total customer time would solve all your problems.

It was enough to drive you into the not-for-profit world.

As the century rolled over, Marketing Management(Spring 1999) concluded, "Practically every company today is geared up to satisfy its customers. 'We do whatever it takes' is the everyday refrain."

Somewhere along the way, customer satisfaction has become a given, not a differentiator.

So, now that we've cleared that up, let's get on with the how-to strategies.

Getting into the mind with a new idea or product or benefit gives you

an enormous advantage. That's because, as described in Chapter 2, minds don't like change.

Psychologists refer to this as "keeping on." Many experiments have shown the magnetic attraction of the status quo. Most decision makers display a strong bias toward alternatives that perpetuate the current situation.

The bottom line: People tend to stick with what they've got. If you meet someone a little better than your wife or husband, it's really not worth making the switch, what with attorneys' fees and dividing up the house and kids.

And if you're there first, when your competitors try to copy you, all they will be doing is reinforcing your idea. It's much easier to get into the mind first than to try to convince someone you have a better product than the one that did get there first.

FIRSTS THAT ARE STILL FIRSTS

Harvard was the first college in America and it's still perceived as the leader.

Time magazine still is the leader over Newsweek. People leads over Us. Playboy leads over Penthouse. Chrysler, which introduced minivans, is still the leader in minivans. Hewlett-Packard leads in desktop laser printers, Sun in workstations, Xerox in copiers. The list goes on and on.

In the mind, the fact that they pioneered the category or product makes them different from their followers. They get a special status because they were the first to the top of the mountain.

This is why Evian, the French mineral water, is spending $20 million on advertising to remind consumers it is l'original.

ATTRIBUTE OWNERSHIP IS A WAY TO DIFFERENTIATE

Attribute is one of those marketing words that is used widely but not really understood. So let's get our definitions straight before we plunge on.

First, an attribute is a characteristic, peculiarity, or distinctive feature of a person or thing. Next, persons or things have a mixture of attributes. Each person is different in terms of sex, size, intelligence, skills, and attractiveness. Each product, depending on the category, also has a set of different attributes. Each toothpaste, for example, is different from other toothpastes in terms of cavity prevention, plaque prevention, taste, tooth whitening, and breath protection.

What makes a person or product unique is being known for one of these attributes. Marilyn Monroe was known for her attractiveness. Crest

toothpaste is known for its cavity prevention. Marilyn might have had a high degree of intelligence, but it wasn't important. What made her special was that pinup beauty. The same with Crest, as it's all about fighting cavities. What it tastes like isn't important.

Attribute ownership is probably the number-one way to differentiate a product or service. But beware, you can't own the same attribute or position that your competitor owns. You must seek out another attribute.

Too often a company attempts to emulate the leader: "They must know what works," goes the rationale, "so let's do something similar." Not good thinking.

It's much better to search for an opposite attribute that will allow you to play off against the leader: The key word here is opposite - similar won't do.

Coca-Cola was the original and thus the choice of older people. Pepsi successfully positioned itself as the choice of the younger generation.

The world of bourbon is dominated by the two Js, Jim Beam and Jack Daniel's. So Maker's Mark set out to own an attribute that makes its smaller sales more attractive: "Handcrafting our bourbon to produce a smooth, soft taste."

Since Crest owned cavity prevention, other toothpastes avoided cavity prevention and jumped on other attributes, such as taste, whitening ability, breath protection, and more recently, inclusion of baking soda.

If you're not a leader, your word has to have a narrow focus. Even more important, however, your word has to be "available" in your category. No one else can have a lock on it.

LEADERSHIP IS A WAY TO DIFFERENTIATE

Leadership is the most powerful way to differentiate a brand. The reason is that it's the most direct way to establish the credentials of a brand. And credentials are the collateral you put up to guarantee the performance of your brand.

Also, when you have leadership credentials, your prospect is likely to believe almost anything you say about your brand(because you're the leader). Humans tend to equate "bigness" with success, status, and leadership. We give respect and admiration to the biggest.

OWNING A CATEGORY

Powerful leaders can take ownership of the word that stands for the category. You can test the validity of a leadership claim by a word-association test.

If the given words are computer, copier, chocolate bar, and cola, the four most associated words are IBM, Xerox, Hershey's, and Coke.

An astute leader will go one step further to solidify its position. Heinz owns the word ketchup. But Heinz went on to isolate the most important ketchup attribute. "Slowest ketchup in the West" is how the company preempted the thickness attribute. Owning the word slow helps Heinz maintain a 50 percent market share.

DON'T BE AFRAID TO BRAG

Despite all of the foregoing points about the power of being the perceived leader, we continue to come across leaders who don't want to talk about their leadership. Their response about avoiding this claim to what is rightfully theirs is often the same: "We don't want to brag."

Well, being a leader who doesn't brag is the best thing that can happen to your competition. When you've clawed your way to the top of the mountain, you had better plant your flag and take some pictures.

And besides, you can often find a nice way to express your leadership. One of our favorite leadership slogans does just that: "Fidelity Investments. Where 12 million investors put their trust."

If you don't take credit for your achievements, the one right behind you will find a way to claim what is rightfully yours.

What companies fail to appreciate is that leadership is a wonderful platform from which to tell the story of how you got to be number one. As we said earlier, people will believe whatever you say if they perceive you as a leader.

DIFFERENT FORMS OF LEADERSHIP

Leadership comes in many flavors, any of which can provide an effective way to differentiate yourself. Here's a quick sampling of different ways to claim leadership:

Sales leadership. The strategy most often used by leaders is to proclaim how well their products sell. The Toyota Camry is the bestselling car in America. But others can claim their own sales leadership by carefully counting sales in different ways. Chrysler's Dodge Caravan is the top-selling minivan. The Ford Explorer is the top sport utility vehicle. This approach works because people tend to buy what others buy. Technology leadership. Some companies with long histories of technological breakthroughs can use this form of leadership as a differentiator. In Austria, the rayon fiber manufacturer Lenzing isn't the sales leader, but it is the "world's leader in viscose fiber technology." The company pioneered many of the industry's breakthroughs in new and improvedHERITAGE IS A DIFFERENTIATING IDEA

In Chapter 2, we discussed the fact that minds are insecure. And any strategy that helps people overcome their insecurities is a good one.

Heritage has the power to make your product stand out. It can be a powerful differentiating idea, because there appears to be a natural psychological importance attached to having a long history, one that makes people feel secure in making a choice.

When we started to study why this is so, we assumed that having been around a long time suggested that a company knew what it was doing. People figured that it must have been doing something right.

But unlike countries such as China and Japan, where elders are given the utmost respect, our culture tends to have an abhorrence of old age. Everybody wants to be young. Old and wise means out of it and passé.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF HERITAGE

When we asked Dr. Carol Moog why heritage is meaningful, the consumer psychologist made the following observations:

The psychological importance of heritage may derive from the power of being a participant in a continuous line that connects and bonds one to the right to be alive, to a history that one carries forward from the living past, through death and on into the next generation. The link is a link to immortality. Without a sense of heritage, of known ancestors, people are vulnerable to feeling isolated, abandoned, emotionally cut off, and ungrounded. Without a line from the past, it is difficult to believe in a line to the future.While that's all very heavy, another way to look at this approach is to recognize that dealing with a company that's been around a long time also gives prospects the feeling that they are dealing with an industry leader. If not the biggest in the industry, it certainly is a leader in longevity.

It's no wonder that marketers display their tradition and culture as a

way of telling you why they are different.

BRING HERITAGE FORWARD

But tradition isn't always enough, says an Associated Press business writer. "Companies of all stripes have spent recent years devising new marketing tactics that blend consumer-comforting tradition with the progressiveness that's crucial to continued success."

Wells Fargo Bank, of Pony Express and stagecoach beginnings, takes its original idea and makes it relevant by simply stating, "Fast then. Fast now." The difference is that today's stagecoaches travel at the speed of light via advanced computer networks.

L.L. Bean jazzes up its catalog, goes online, and introduces women's clothing - while carefully maintaining its New England image. Says a company spokesperson, "You take the classic appeal and you take it to another generation."

The continued success of Tabasco in the pepper sauce business is an example of the balance between honoring your heritage and looking forward.

Its advertising strikes traditional themes such as down-home Louisiana bayous and pepper mash aged in oak barrels. But the company also presents itself as with-it and trendy, with Tabasco neckties, Cajun cooking festivals, and new Tabasco-laced drinks that originated in rural Louisiana oyster bars.

One popular drink is the prairie fire, which combines a shot of tequila with a splash of Tabasco.

"There are all sorts of balancing acts needed in marketing," says company president Paul C. P. McIlhenny.

Well said. He's balancing the old with the new.

FAMILY HERITAGE

In a world that's seeing the big get bigger, an effective way to separate yourself from the striving herd is to keep your business a family business. While taxes and ensuing generations don't always make this easy, family heritage can be a powerful concept if the family can be held together.

People seem to feel more kindly toward a family-run business as opposed to a cold, impersonal public corporation that's beholden to a bunch of greedy stockholders. Family members can be just as greedy. But, because what goes on is never reported, all that greed is kept behind closed doors.

Family businesses are also believed to be more involved with their product than with their stock price. They also are given higher marks for community involvement, because the family members tend to be natives of the town where the company was founded. We've also discovered that family businesses tend to treat their employees more like family. There's a feeling of having grown up together.

HOW A PRODUCT IS MADE CAN BE A DIFFERENTIATING IDEA

Companies tend to work very hard in developing new products. Hordes of engineers, designers, and manufacturing people spend endless hours producing and testing what they feel is a unique product that does its job better than anything in the market.

But all that work is often taken for granted by the marketing folks, who get swept away in their own activities, such as advertising, packaging, and promotion.

We're great believers in digging into a product to find out exactly how it works. More times than not we find a powerful differentiation idea that has been ignored.

THE MAGIC INGREDIENT

Many products contain a piece of technology or a design that makes them function. Often, this technology is patented. Yet marketing people tend to dismiss these elements as too complex or too confusing to explain to customers. They would rather conduct research and focus on the benefits or the lifestyle experience of the product. Their favorite speech goes like this: "People don't care how it's made. They only care about what it does for them."

The problem with this point of view is that in many categories, a number of products do the same thing for people. All toothpastes prevent cavities. All new cars drive very nicely. All detergents clean clothes. It's how they are made that often makes them different.

This is why we like to focus on the product and locate that unique piece of technology. Then, if possible, we give that design element a name, and if we can package it as a magic ingredient, all the better.

When Procter & Gamble introduced Crest toothpaste with fluoride for cavity prevention, the ad campaign made sure everyone knew it contained "fluoristan." Did anyone understand what that was? Nope. Did it matter? Nope. It just sounded impressive.

When Sony began its dominance in television, it made a fuss about the "Trinitron" picture tube. Did anyone understand what it was? Nope. Did it matter? Nope. It just sounded impressive.

General Motors has probably spent over $100 million promoting the Northstar system used in Cadillacs. Does anyone understand how this engine works? Nope. Does it matter? Nope. It just sounds impressive.

Magic ingredients don't have to be explained, because they are magic.

MAKING IT THE RIGHT WAY

Often, there is a wrong way and a right way to make a product. The wrong(or less desirable) way is often introduced as a money-saving process. Consultants like to call this "improving manufacturing practices"(translation: cutting costs). The right way absorbs the higher costs so as to produce a better product.

There are times, if an industry is going the wrong way, when you can be different by going the right way. Such was the case for Stanislaus Food Products. The company has become the leading manufacturer of tomato sauce for a large number of America's Italian restaurants. And it has accomplished this while charging higher prices. The winning strategy was not to follow the industry into concentrated tomato sauce(which is cheaper to make and to ship).

Dino Cortopassi, the owner of the company, felt that the fresh-packed method, in which the sauce was never put through the concentration process, was a better way to make this product. It costs more, but the sauce tastes better.

That's his difference. And much to his competitors' dismay, most of the real Italian restaurants in America agree with him.

MAKING IT THE OLD-FASHIONED WAY

A similar story comes from Aron Streit Inc., the last independent matzo company.(For those who aren't sure, matzo is the authentic, unleavened, unsalted, and un-everything else bread that kept the Israelites alive on their flight from Egypt.)

Even though the company has only a small share of a market dominated by B. Manischewitz, the Streit's Matzo folks realize that tradition is about all that distinguishes one matzo from another. Despite all the trendy outsourcing for many of its other products, Streit's still makes its matzos on Rivington Street in lower Manhattan - the same place where the company has made them since 1914.

If you go to Streit's Web site, Streitsmatzos.com, you'll discover that the company knows what the difference is all about. Here's how Streit's puts it: "Why is Streit's Matzo different from other domestic matzo brands? Because Streit's bakes only Streit's Matzo in our own ovens."

They still make their matzo the old-fashioned way.

When you're hot, the world should know you're hot. As you saw in Chapter 2, people are like sheep. That's why they love to know what's hot and what's not. It's also why word of mouth is such a powerful force in marketing. That word of mouth usually consists of one person telling another person what's hot. This is important, for while America loves underdogs, people bet on the winners.

FEAR OF BOASTING

Unfortunately, many companies are shy in telling the world about their success. First they say that boasting isn't nice. It's pushy. It's bad manners. But what's really behind this reluctance is a fear that they won't stay hot forever. And then what? Won't they be embarrassed?

What I'm trying to explain is that getting a company or product off the ground is like launching a satellite. What you often need is some early thrust to get you into orbit. After that, it's a different game.

Being hot or experiencing sales growth beyond that of your competitors can give you the thrust you need to get your brand up to altitude. Once there, you can figure out something else to keep you there.

MANY WAYS TO BE HOT

When you're using a "hotness" strategy, you have the opportunity to define why you're hot. What many don't realize is that there are many ways to structure that definition. Here's a roundup of the most popular ways:

Sales. The most often used approach is to compare your sales to your competitors' sales. But don't think you have to compare annual sales. You can use any time period you choose: 6 months, 2 years, 5 years. The time you choose to measure is the one that makes you look best. Remember that you are free to pick the parameters. Also, you don't have to compare yourself to your competitors. You can compare yourself to yourself. Industry ratings. Most industries have annual ratings for performance. They could be administered by industry magazines such as Restaurant News or consumer magazines such as U.S. News & World Report or organizations such as J.D. Powers. If you win a rating from one of these, use it as aggressively as possible. Industry experts. Some industries have experts or critics who are often quoted or who write widely read columns. This is especially true in the high-tech world, where you have Esther Tyson and the Gartner Group, for example. Sometimes you can use their quotes or reports as a way to define your success. Hollywood uses this device to establish a hot movie, as does the publishing world for a hot book.THE PRESS CAN MAKE YOU HOT

While it's helpful to blow your own horn, it's even better if you can get someone else to do it. This is where an aggressive public relations program can pay big dividends.

What's afoot here is the fact that "third-party" credentials are very powerful. Whether the third party is your neighbor or your local newspaper, people feel that these sources are unbiased. So when they say you're hot, you must indeed be hot.

Creating a success in public relations is like throwing a rock into a pond. The circles start small but spread throughout the pond. You start with the experts, spread to the trade papers, and expand out to the business and consumer press.

But before you talk to the press, you've got to work out your program. Here are all the steps.

Step 1: Make sense in the context. Arguments are never made in a vacuum. There are always surrounding competitors trying to make arguments of their own. Your message has to make sense in the context of the category. It has to start with what the marketplace has heard and registered from your competition.

Step 2: Find the differentiating idea. To be different is to be not the same. To be unique is to be one of a kind. So you're looking for something that separates you from your competitors. The secret to this is understanding that your differentness does not have to be product related. But it should set up a benefit for your customer.

Step 3: Have the credentials. To build a logical argument for your difference, you must have the credentials to support your differentiating idea, to make it real and believable.

If you have a product difference, then you should be able to demonstrate that difference. The demonstration, in turn, supplies your credentials. If you have a leak-proof valve, then you should be able to have a direct comparison with valves that can leak.

Claims of difference without proof are really just claims.

Step 4: Communicate your difference. Just as you can't keep your light under a basket, you can't keep your difference under wraps.

If you build a differentiated product, the world will not automatically beat a path to your door. Better products don't win. Better perceptions tend to be the winners. Truth will not out unless it has some help along the way.

Every aspect of your communications should reflect your difference:

SUMMATION

••••••••••••••••••••••••••

If you don't have

a point of difference,

you'd better have a low price.

Strategy Is All about Competition

As you just read in Chapter 3, you start your strategic planning with your competition in mind. Where are they strong? Where are they weak? The reason you start this way is because business today is not about reengineering or continuous improvement. Business is about war. It's not about better people and better products.

THE "BETTER PEOPLE" FALLACY

It's easy enough to convince your own staff that better people will prevail, even against the odds. It's what they want to hear. And surely, in a marketing war, quality is a factor as well as quantity.

It is, but superiority of force is such an overwhelming advantage that it overcomes most quality differences.

We have no doubt that the poorest team in the National Football League could consistently beat the best team in the NFL if it could field 12 men against the opposition's 11.

In business, where the teams are much larger, the ability to amass a quality difference is much more difficult to achieve.

The clear-thinking manager won't confuse the pep talk at a sales rally with the reality of the marketing arena. A good general never makes military strategy based on having better personnel. Nor should a business general.

Tell your people how terrific they are, but don't plan on winning the battle with superior personnel.

Count on winning the battle with a superior strategy.

Yet many companies cling deeply to the better people strategy. They're convinced they can recruit and hire substantially better people than the competition can, and that their better training programs can help them keep their "people" edge.

Any student of statistics would laugh at this belief. Sure, it's possible to put together a small cadre of superior people. But the larger the company, the more likely the average employee will be average.

And when it comes to the megacompanies, the possibility of assembling an intellectually superior team becomes statistically almost zero.

THE "BETTER PRODUCT" FALLACY

Another fallacy ingrained in the minds of most managers is the belief that the better product will win the marketing battle.

Behind the thinking of many marketing managers is the idea that "truth will out."

In other words, if you have the "facts" on your side, it's only necessary to find a good advertising agency that can communicate those facts to the prospect and a good sales force that can close the sale.

We call this approach inside-out thinking - the idea that somehow the advertising agency or the sales force can take the truth, as the company knows it, and use this truth to clear up the misconceptions that reside inside the mind of the prospect.

Don't be fooled. Misconceptions cannot easily be changed by an advertising or sales effort.

What is truth? Inside every human being is a little black box. When a human being is exposed to your advertising or sales claim, that person looks inside the box and says "That's right" or "That's wrong."

The single most wasteful thing you can do in marketing today is to try to change a human mind. Once a mind is made up, it's almost impossible to change.

What is truth? Truth is the perception that's inside the mind of the prospect. It may not be your truth, but it's the only truth you can work with. You have to accept that truth and then deal with it.

IF YOU'RE SO SMART, HOW COME YOU'RE NOT RICH?

Even if you succeed in convincing the prospect that you have a better product, the prospect soon has a second thought: "Hey, if your computer is better than IBM's, how come you're not the leader, like IBM is?"

Even if you get a few black boxes to go along with you, the owners of

those black boxes soon let the unsold majority sway their judgment.

If you're so smart, how come you're not rich? That's a tough question to answer. In a marketing war, you can't win just by being right.

There's the illusion, of course, that over the long run, the better product will win. But history, military and marketing, is written by the winners, not the losers.

Might is right. Winners always have the better product, and they're always available to say so.

MARKETING AS WAR

Al Ries and I first presented this observation more than 25 years ago in a book titled Marketing Warfare. In hindsight, this book was published in the dark ages of competition. A decade ago, the term global economy wasn't talked about very much. The vast array of technology that we take for granted was still a glimmer in the eyes of some Silicon Valley engineers. Global commerce was pretty much limited to a handful of multinational companies.

As we entered the new millennium, of the world's 100 largest economies, 51 were not countries but corporations. The 500 largest accounted for a stunning 70 percent of world trade.

Today's marketplace makes the one we first wrote about look like a tea party. The wars are escalating and breaking out in every part of the globe. Everyone is after everyone's business everywhere.

All this means that the principles of Marketing Warfare are more important than ever. Companies must learn how to deal with their competitors - how to avoid their strengths and how to exploit their weaknesses. Organizations must learn that it's not about do or die for your company. It's about making the other guy die for his company.

A CHANGE OF PHILOSOPHY

The classic definition of marketing leads one to believe that marketing has to do with satisfying consumer needs and wants.

Marketing is "human activity directed at satisfying needs and wants through exchange processes," says Philip Kotler of Northwestern University.

Marketing is "the performance of those activities which seek to accomplish an organization's objectives by anticipating customer or client needs and directing a flow or need-satisfying goods and services from producer to customer or client," says E. Jerome McCarthy of Michigan State University.

Marketing people traditionally have been customer-oriented. Over and over again they have warned management to be customer- rather than production-oriented.

Ever since World War II, King Customer has reigned supreme in the world of marketing.

But it's beginning to look like King Customer is dead. And marketing people have been selling a corpse to top management.

That's because today, every company is customer-oriented. Knowing what the customer wants isn't too helpful if a dozen other companies are already serving the same customer. General Motor's problem is not the customer. General Motor's problem is Ford, Chrysler, and the imports.

BECOMING COMPETITOR-ORIENTED

To be successful, a company must become competitor-oriented. It must look for weak points in the positions of its competitors and then launch marketing attacks against those weak points.

There are those who would say that a well-thought-out marketing plan always includes a section on the competition. Indeed it does. Usually toward the back of the plan in a section titled "Competitive Evaluation." The major part of the plan usually spells out the details of the marketplace, its various segments, and a myriad of customer research statistics carefully gleaned from endless focus groups, test panels, and concept and marketing tests.

In the marketing plan of the future, many more pages will be dedicated to the competition. This plan will carefully dissect each participant in the marketplace. It will develop a list of competitive weaknesses and strengths as well as a plan of action to either exploit or defend against them.

There might even come a day when this plan will contain a dossier on each of the competitors' key marketing people, which will include their favorite tactics and style of operation(not unlike the documents the Germans kept on Allied commanders in World War II).

What does all this portend for marketing people of the future?

It means they'll have to be prepared to wage marketing warfare. More and more, successful marketing campaigns will have to be planned like military campaigns.

Strategic planning will become more and more important. Companies will have to learn how to attack and to flank their competition, how to defend their positions, and how and when to wage guerrilla warfare. They will need better intelligence on how to anticipate competitive

moves.

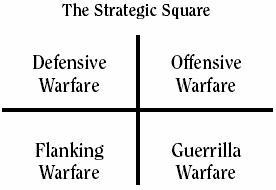

It's all about pursuing the right competitive strategy. It's all about understanding the four types of marketing warfare shown in the accompanying diagram "the strategic square" and figuring out which applies to your situation.

These principles constitute a very simple strategic model for company survival in the twenty-first century. Let's review and update them.

1.

Defensive warfare is what market leaders wage. Leadership is reserved for those companies whose customers perceive them as the leader.(Not as pretenders to being leaders.)

Your most aggressive leaders are willing to attack themselves with new ideas. We have long used Gillette as a classic defender. Every 2 or 3 years it replaces its existing blade with a new idea. We've had two-bladed razors(Atra). We've had shock-absorbent razors(Sensor). And now we have three-bladed razors(Mach 3). A rolling company gathers few competitors.

An aggressive leader always blocks competitive moves. When Bic introduced the disposable razor, Gillette quickly countered with the twin-bladed disposable(Good News). It now dominates this category.

All this adds up to over 60 percent of the blade market. That's a leader.

2.

Offensive warfare is the strategy for the number-two or -three business in a category. The first principle is to avoid the strength of the leader's position. What you want to do is find a weakness and attack at that point. Then you focus all your efforts at that point.

In recent years, the fastest-growing pizza chain in America has been Papa John's Pizza. Papa John's attacked Pizza Hut at its weak point, ingredients. John Schnatter, the founder, got his hands on the best tomato sauce in the country. It was a sauce that the other chains couldn't buy. This became the cornerstone of his concept: "Better Ingredients. Better Pizza."

Schnatter has stayed narrowly focused on the better-ingredients concept in everything he uses, such as cheese and toppings. He even filters the water for better dough.

As the Wall Street Journal reported, "Papa John's is on a tear." This is not the kind of news that Pizza Hut is very happy about.

One of the best ways of attacking a leader is with a new-generation technology.

In the land of paper making, quality control systems have become a two-horse race between Measurex, the current leader, and AccuRay(a part of Asea Brown Boveri), the former leader in systems that measure the uniformity of paper as it is produced.

AccuRay attacked Measurex with a new generation of electronic scanning technology that measures the entire sheet instead of just parts of the sheet. This new weapon is called Hyper Scan Full Sheet Imaging, and it

promises a quality control measurement that Measurex can't measure up to. This idea will work because AccuRay just made its competitor obsolete. 3. New or smaller players that are trying to get a foothold in a category by avoiding the main battle pursue flanking warfare. This strategy usually involves a move into an uncontested area and includes the element of surprise. Often it's a new idea, such as gourmet popping corn(Orville Redenbacher) or Dijon mustard(Grey Poupon). A brilliant flanking move has been under way in the golf world. While others have focused on drivers, irons, and putters, Adams Golf has gone into an area that has never been heavily contested.(It lies in the fairway about 200 yards from the green.) Adams's flanking move was to introduce a patented flat design of fairway woods that were perfect for those tight lies. The simple but brilliant product name says it all: Tight Lies Fairway Woods. Very quickly, they became the fastest-growing fairway woods in the country. When a 19-year-old named Michael Dell started his own little computer company, he knew he couldn't compete with established companies for floor space in stores. However, the rules of the industry, at that time, dictated that computers had to be sold in stores. Every company in the industry believed that customers wouldn't trust a mail-order company to provide such a high-end item. Dell broke the rule. He flanked the industry with direct marketing. And he built an $800 million company in 5 years. 4. Guerrilla warfare is often the land of the smaller companies. The first principle is to find a market small enough to defend. It's the big fish in the small pond strategy. No matter how successful you become, never act like a leader. Going big-time is what does in successful guerrilla companies.(Anyone remember People's Express Airlines?) Finally, you have to be prepared to bug out at a moment's notice. Small companies can't afford to take those losses. Melt into the jungle so you can live to fight another day. One of the most interesting guerrilla case studies is under way down in the Caribbean. This is where the tourism wars are being waged by all the islands, big and small. Grenada is one of the southernmost islands in the Caribbean. Famous for President Reagan's invasion to expel a few Cubans, Grenada is now trying to get a share of the tourist business. Because it's late in the game, the island is unspoiled. There is little concrete, and there are no overdeveloped beaches. In fact, there are no buildings higher than a palm tree. That has enabled Grenada to develop a strategy of being the unspoiled island, or "the Caribbean the way it used to be." This is a defensible idea, because all the other islands are developed. There's no way they can suddenly become unspoiled. But smaller jungle fighters must be aware of the fact that the jungle can become an overpopulated